Andrew Hallam

22.06.23

Why High Dividend Paying Stocks Are Overrated

_

“Just buy a handful of high dividend stocks or a high-dividend paying ETF. It’s relatively safe, and you’ll beat a broad market index fund. It’s an even better strategy for retirees.”

You’ve probably heard this…maybe a lot. But unfortunately, it isn’t true.

In the 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s, index funds didn’t exist so many people bought individual shares.

Most of those people, however, preferred watching Dr. Who to digging into company annual reports. Few sifted through corporate tax information; accounts receivables; net and gross profit margins to see if a company was solid.

Yet these investors weren’t fools. They figured that if a company could afford to pay high cash dividends, it should be on solid ground.

Index funds, however, changed the game. As a group, high dividend paying stocks don’t beat broad stock market indexes and they’re less tax efficient.

Imagine this:

I’m worth $1 billion.

I then give you $100 million.

Am I still worth $1 billion?

No.

I’m now worth $900 million.

The same thing happens when a company pays a dividend. The company reduces its intrinsic value directly in proportion to the dividend paid.

That doesn’t mean its stock price will drop. But long term, a stock’s price increase is directly related to the rise in that company’s intrinsic value. The more money that company gives away in dividends, the less potential its share price has to grow.

IBM is an extreme example that helps to prove this point. It has paid quarterly dividends without interruption since 1916 and has increased its dividend payout 28 years in a row. As I write this, it pays a dividend yield of 5.38 percent.

If you invested $10,000 in IBM shares in 1986, and reinvested all dividends, your money would have grown to about $88,000 by May 19th, 2023.

If, on the other hand, you invested $10,000 in Vanguard’s S&P 500 stock market index and reinvested all dividends, it would have grown to about $430,000.

IBM’s high dividends gave investors a warm, fuzzy feeling. But those dividends hurt investors. That’s because IBM paid its shareholders a lot of money every year that it could have invested efficiently in its own internal operations.

For example, as shown in the table below, IBM paid its shareholders 43 percent of every dollar the company earned in 2017. That’s a lot. As a result, IBM was only able to reinvest 47 percent of its profits into its own business ventures.

The “Return on Total Capital” measures what a company earns internally. In 2017, IBM’s return on total capital was an impressive 22.9 percent. Most years, as shown on the table, that rate is even higher.

So, while shareholders felt good about earning a high dividend, if IBM paid out less, it could have reinvested more money internally. That would have increased IBM’s intrinsic value. And over time, increases in intrinsic value correlate with higher share prices.

Below, I’ve listed the percentage of annual profits that IBM gave shareholders each year between 2011 and 2022. I also included the rate of return IBM made on the money it retained and reinvested in its business. Based on the high rates of return on total capital, paying shareholders so much in dividends actually hurt investors.

That’s one of the reasons a $10,000 investment in IBM, including dividends, only grew to about $88,000 from 1986 to 2023; whereas, the same investment in the S&P 500 grew to about $430,000.

When High Dividends Hurt Investors

IBM (International Business Machines)

2011 – 2022

| Year | Percentage of Profits Given To Shareholders | Return On Total Capital (profits earned on money retained by the company) |

|---|---|---|

2011 | 22% | 37.6% |

2012 | 23% | 39.5% |

2013 | 25% | 30.4% |

2014 | 27% | 34.6% |

2015 | 37% | 28.4% |

2016 | 44% | 23.4% |

2017 | 43% | 22.9% |

2018 | 45% | 24.9% |

2019 | 50% | 16.4% |

2020 | 75% | 11.4% |

2020 | 61% | 14% |

2022 | 58% | 14.5% |

Source:1

Warren Buffett says companies that earn high rates of return on total capital shouldn’t pay high dividends. Doing so wastes shareholders’ money. 2

This is why Buffett’s company doesn’t pay a dividend. Berkshire Hathaway has earned a high rate of return on total capital (much like IBM). But instead of giving the money to shareholders, he has reinvested that money. This has increased Berkshire Hathaway’s share price over time, allowing it to outperform every high-dividend paying stock since 1965 (when Warren Buffett took the helm).

You might wonder, then, why IBM pays high dividends.

When shareholders get used to seeing dividend increases, corporate executives don’t want to disappoint them. Doing so could temporarily drop the share price (if investors sold). This can have dramatic short-term consequences on executives’ stock options or on executives’ popularity among corporate board members.

IBM, however, is a dramatic case. Most high dividend paying stocks haven’t performed this badly. That’s because most of them retain a far higher percentage of their profits, compared to IBM.

But that doesn’t mean they beat broad stock market indexes.

Get International Investing insights

in your inbox once per month

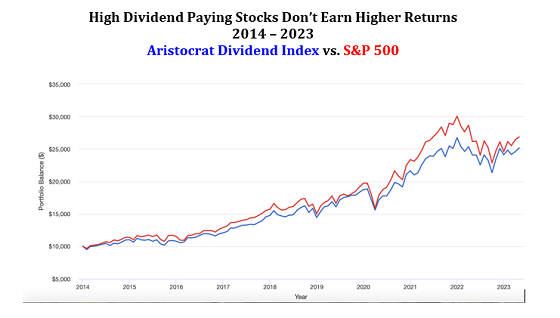

In late 2013, Vanguard created its Dividend Appreciation Index fund, catering to investors’ desire for high dividend paying stocks. Each of the companies in this index has a long history of increasing dividend payouts. But in a tax-free account, with all dividends reinvested, it underperformed the S&P 500.

Source: portfoliovisualizer.com

To be fair, ten years is a blip. But the longer- term data reveals much the same thing. As a group, high dividend paying stocks don’t beat the market, even when dividends are reinvested. This is why Dimensional Fund Advisors agrees that higher dividends don’t lead to better returns.3

Benjamin Felix, of PWL Capital explains much the same thing in this video.

What’s more, investors living in capital-gains free jurisdictions (such as Luxembourg, the UAE, Malaysia and Singapore, to name just four examples) would pay an even higher price to own high dividend paying stocks.

Here’s why:

When a business (like Apple, for example) earns a corporate profit, it pays corporate tax on that profit. This tax (like any business cost) reduces Apple’s intrinsic value, much as a dividend payout does.

Investors who receive high dividends (any dividends, in fact) pay a second tax on that dividend. It might be a tax of 15 to 30 percent, depending on the origin of the stock (or the stock within their index). In most cases, investors don’t see this tax taken out. But it comes out of the investor’s dividend proceeds.

As Warren Buffett explains, 2 investors are taxed twice: once at the corporate level (affecting the intrinsic value of the business) and once in the form of a dividend tax. The higher the dividend payout, the more absolute tax that’s taken.

Residents in capital-gains free jurisdictions, however, don’t pay capital gains taxes. So when a company retains a higher percentage of its earnings, the increase in the share price (caused by an increase in the company’s intrinsic value) doesn’t attract capital gains taxes when the investor sells.

And if they repatriate to a country where they will pay capital gains taxes, such taxes typically attract lower tax rates than dividends themselves. 4

This is why, even for retirees, it’s better to own a globally diversified portfolio of index funds…and not fall in love with high dividend paying stocks.

Sources:

1. The Valueline Investment Survey

2. The Essays of Warren Buffett: Lessons for Corporate America

3. Yields of Dreams: A Closer Look at Dividends

4. Most British Expats Are Wrong About the Taxes They’ll Pay After Moving Back to Britain

Andrew Hallam is a Digital Nomad. He’s the bestselling author Balance: How to Invest and Spend for Happiness, Health and Wealth. He also wrote Millionaire Teacher and Millionaire Expat: How To Build Wealth Living Overseas

Swissquote Bank Europe S.A. accepts no responsibility for the content of this report and makes no warranty as to its accuracy of completeness. This report is not intended to be financial advice, or a recommendation for any investment or investment strategy. The information is prepared for general information only, and as such, the specific needs, investment objectives or financial situation of any particular user have not been taken into consideration. Opinions expressed are those of the author, not Swissquote Bank Europe and Swissquote Bank Europe accepts no liability for any loss caused by the use of this information. This report contains information produced by a third party that has been remunerated by Swissquote Bank Europe.

Please note the value of investments can go down as well as up, and you may not get back all the money that you invest. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.