Andrew Hallam

01.02.2021

Investors’ Great Expectations for Disruptive Technologies

_

George Gilder was God. At least, that’s what we thought. Gilder described a new paradigm that promised to change the world and commerce in magnitudes akin to the printing press, air travel, the telephone and electricity.

We hung on every word of the Gilder Technology Report, which he created in 1996. It included impressive research and technical explanations that predicted much of what came to be. The report’s back page, however, was what we clamored for every month. It included a list of game-changing stocks: “telecosmic” companies that embraced what he called, the “ascendant” telecom technologies.

We shoveled his stocks into our investment club portfolio and we soon made a fortune. He liked stocks like Globalstar, a company that offered satellite communications systems. With a Globalstar phone, you didn’t have to worry about wonky inconsistent reception from cell towers. With Globalstar’s direct satellite linkage (the first of its kind) people could call their loved ones from the North Pole or the depths of The Grand Canyon.

Gilder also recommended Optibase, a company with video streaming technology. It was Netflix before Netflix. This was going to revolutionize the way we watch movies.

Gilder liked Global Crossing too. It lay underwater fiber optics cable which connected the planet to WiFi. He also recommended Nortel Networks, JDS Uniphase, Lucent Technologies, Novell, Intel, International Rectifier (we giggled at that name) and Cisco Systems.

In so many ways, Gilder was right. And the stocks he recommended hit stratospheric heights. My friend, Grant, allocated about 80 percent of his personal portfolio to Gilder’s stocks. We watched in amazement as Grant quadrupled his money in less than one year. “I’m in this for the long haul,” Grant said. “These technologies are changing, and will continue to change the world.” Grant was right. And Gilder was right…until he wasn’t. From 2000-2002, Gilder’s stocks lost about 90 percent. Investors who bought them in 2000 would have needed to gain 800 percent from the low in 2002, just to break even. And that gain never came.

Global Crossing went belly up. Optibase (Netflix before Netflix) couldn’t gain traction so it went into property investments. Nortel Networks (a global leader in fiber optics networks) went bankrupt.

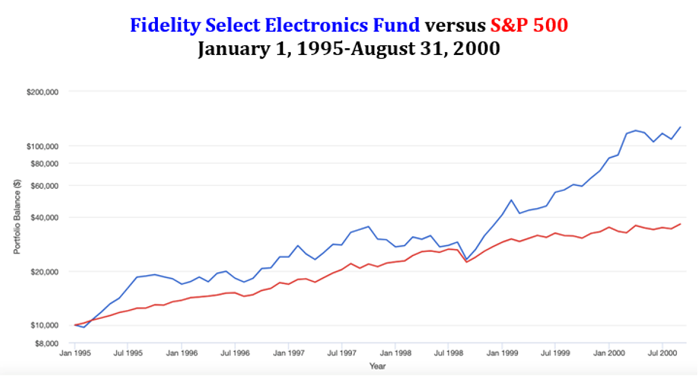

But let’s back up to that pre-crash wave. Financial analysts who supported the technological paradigm became household names. We hung on the words of Morgan Stanley’s Mary Meeker, Solomon Smith Barney’s Jack Grubman and Merrill Lynch’s Henry Blodgett. If Gilder was God, these were the Apostles. This new era cared little for current profits. Yet we were visionaries. We knew business profits might not come right away. But as visionaries, we believed the analysts. The future, at the time, looked so darn obvious. And because our stock prices soared, we thought we (and “the experts”) were right. Plenty of mutual funds filled with Gilder-like stocks. For example, the Fidelity Select Electronics Fund (now called the Fidelity Select Semiconductors Fund) gained 1,116 percent from January 1, 1995 to August 31, 2000. That was a compound annual return of 56.4 percent. Anyone who invested $10,000 in the fund in 1995 would have seen it grow to $126,353. This proved genius. At least, that’s what we thought.

Source: portfoliovisualizer.com

Unfortunately, something else was happening. Historically, whenever a new technology serves to disrupt life or business, it draws curiosity and projections about the future. That entices people to speculate. When demand for such shares increases, more investors jump on board. Others, who then see share prices rise, toss their money into the race. Then FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) causes a stampede of buyers. That pushes share prices further. Converts say, “Current earnings don’t matter. Only future projections count.”

Historically, this results in bubbles and subsequent crashes. Carlota Perez outlines this well in the Cambridge Journal of Economics: The Double Bubble at the Turn of the Century, technological roots and structural imperfections.

The challenge is four-fold:

1. Find the right disruptive technology.

2. Find a business in that niche that is making profits now or will very soon.

3. Predict a durable competitive advantage for that business to fight off competition.

4. Buy that business at the right price.

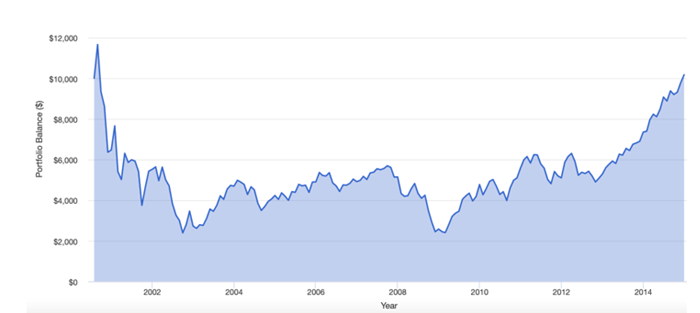

Like Gilder’s followers, people who bought mutual funds like Fidelity Select Electronics Fund in 2000 crashed hard. Some of those businesses were great. But investors paid too much for them. It took 15 years for the fund to eclipse its 2000 level. Unfortunately, few of that fund’s investors enjoyed the 1,116 percent growth from 1995-2000 because they bought late in flight. Most of the money piled in between 1999 and 2000. This is common with high-flying funds.

When A Can’t-Miss Fund Burns Investors

Fidelity Select Electronics Fund

2000-2015

Source: portfoliovisualizer.com

These days, George Gilder keeps pretty quiet. But 64-year old Cathie Wood certainly does not. She excited a new generation of investors with another paradigm. She’s responsible for the investment decisions at ARK Invest.

Like Gilder and the tech-minded apostles of the past, she doesn’t concern herself with businesses that make profits now. Instead, she picks companies that she hopes will make profits later.

And the stocks in her fund have soared on the excitement. Over the five years ending December 28, 2020, her ARK Innovation fund gained 599 percent. In 2020, it gained 158 percent. Most of the fund’s holdings, however, don’t yet earn corporate profits.

ARK Innovation Top Ten Holdings

December 28, 2020

| Stocks | Q1 Net Profits | Q2 Net Profits | Q3 Net Profits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tesla (TSLA) | 16 million | 104 million | 331 million |

| Roku (ROKU | -54.6 million | -43.14 million | 12.9 million |

| CRISPR Therapeutics (CRSP) | -69.7 million | -79.65 million | -92.43 million |

| Square (SQ) | -105.89 million | -11.47 million | +36.5 million |

| Invitae (NVTA) | -98.52 million | -166.4 million | -102.9 million |

| Teladoc Health (TDOC) | -29.6 million | -25.6 million | -35,8 million |

| Editas Medicine (EDIT) | -37.7 million | -25.5 million | 7,8 million |

| Zillow Group (Z) | -163.2 million | -84.4 million | 39.5 million |

| Proto Labs (PRLB) | 13.9 million | 12.6 million | 14.69 million |

| Pure Storage (PSTG) | -90.5 million | -64.9 million | -74.2 million |

Measured in USD

Sources: Yahoo Finance and ARK Invest

This doesn’t mean the Ark funds are destined to crash. Plenty of investors say this time is different. Umair Bilal is one of them. The documentary filmmaker and university film instructor has been a stock market investor for the past five years. “I bought all 5 ARK ETFs in June of this year,” he says. “I am up more than 100 percent in ARK funds overall.” He adds, “We have not seen the type of innovation happening as of late for more than a century. The last time that we saw a similar convergence of technology was in late 1800s with the advent of telecommunication, telephone and [the] internal combustion engine, which transformed the world entirely and seeped into every sector.”

Fifty-two year old Elizabeth Meffen agrees. Like Umair Bilal, she also started to buy Ark funds in June. She currently owns the Ark Next Generation Internet ETF (ARKW); The Ark Fintech Innovation ETF (ARKF); The Ark Genomic Revolution (ARKG) and the Ark Innovation ETF (ARKK). “I have done a lot of research into Cathie Wood,” she says, “and I like her vision, as well as a strategy that is very much embracing …what tomorrow will look like, as opposed to purely focusing on near term gains.”

Umair Bilal and Elizabeth Meffen say they expect to earn at least 20 percent a year over the next ten years. As for me, this all feels a lot like déjà vu. I’ll watch with fascination and stick to my portfolio of low-cost index funds.

Andrew Hallam is a Digital Nomad. He’s the author of the bestseller, Millionaire Teacher and Millionaire Expat: How To Build Wealth Living Overseas

Swissquote Bank Europe S.A. accepts no responsibility for the content of this report and makes no warranty as to its accuracy of completeness. This report is not intended to be financial advice, or a recommendation for any investment or investment strategy. The information is prepared for general information only, and as such, the specific needs, investment objectives or financial situation of any particular user have not been taken into consideration. Opinions expressed are those of the author, not Swissquote Bank Europe and Swissquote Bank Europe accepts no liability for any loss caused by the use of this information. This report contains information produced by a third party that has been remunerated by Swissquote Bank Europe.

Please note the value of investments can go down as well as up, and you may not get back all the money that you invest. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.