"There is no such thing as infallible technology"

While seen as extremely reliable, biometrics does have its weaknesses. At Idiap, a research institute in Martigny, researchers test and improve the security of biometrics systems.

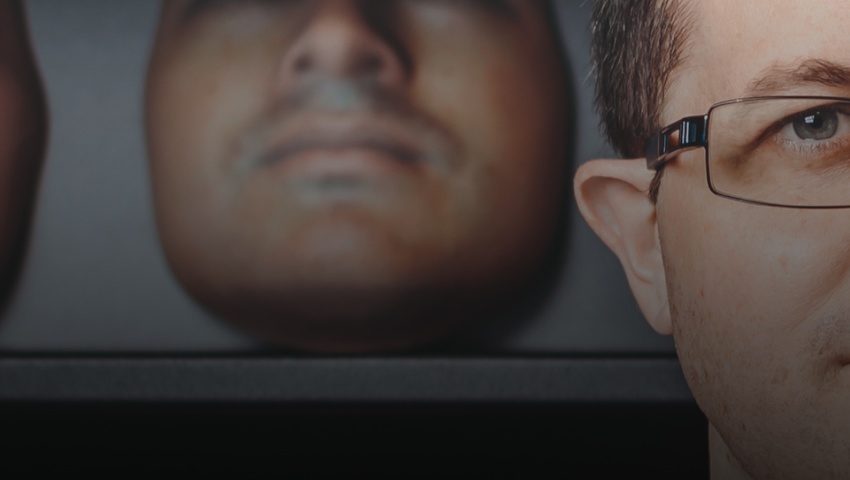

Image: Professor Sébastien Marcel, head of the Biometrics Security and Privacy research group at Idiap, poses in front of silicone masks. Idiap uses these to test and improve facial recognition systems.

By Bertrand Beauté

In 2017, Apple proudly unveiled the new iPhone X, the brand’s first smartphone equipped with Face ID, its facial recognition software. One week later, the Vietnamese company Bkav, which specialises in information security, put out a press release stating that it hacked Face ID by using a handmade mask created with a 3D printer. There are similar hacking success stories for every type of biometrics technology. In an article published in Vice in February 2023, journalist Joseph Cox described how he fooled the voice recognition system at his bank, Lloyds Bank, with an AI-generated voice sample. Fingerprints aren’t immune, either: in 2021, Kraken Security Labs demonstrated how easy it was to reproduce a fingerprint and make a copy that can fool the biometric sensors embedded in our devices (i.e., smartphones, tablets and computers).

"All the big smartphone manufacturers, but also governments and corporations, come to us to have us test their products"

Sébastien Marcel, head of the Biometrics Security and Privacy research group at Idiap

Is the infallible security promised by biometrics nothing more than a mirage? To answer this question, we went to Martigny to visit the Idiap Research Institute. In April 2023, biometrics industry leaders (academics and companies alike) from around the world gathered here in the foothills of the Valais mountains. While lesser known to the general public than ETHZ or EPFL, Idiap is a world-class biometrics institute. "We have very unique expertise," says Sébastien Marcel, head of the Biometrics Security and Privacy research group at Idiap. "All the big smartphone manufacturers, but also governments and corporations, come to us to have us test their products." The names of these manufacturers will remain a secret, as outlined in each confidentiality agreement.

What we do know is that Idiap has been accredited since 2019 by the FIDO (Fast IDentity Online) Alliance, which includes many companies, including Big Tech (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft) and payment systems providers such as Visa, Mastercard and PayPal. The Valais-based institute is one of twelve laboratories in the world that are authorised to test and certify biometrics systems. In 2020, Idiap was also recognised by Android (Google) to certify the biometrics systems used in its ecosystem. App providers that use Android authentication technologies can have their work tested and approved at Martigny.

"Even with their significant financial resources, big tech giants can’t do everything," says Marcel. "And so multinationals come to us. We first try to hack their biometrics system and then provide solutions to make them more secure. Even though we work with lots of corporations, we remain completely independent. We are not affiliated with any company."

So, are current systems reliable? "Generally speaking, yes, but there’s no such thing as infallible technology," says Marcel. "With smartphones, for example, ideally we would want the system to always recognise its owner and never recognise anyone else. But in reality, that’s impossible: a biometrics system that recognises its owner 100% of the time would sometimes let other people in. Conversely, a system that rejects 100% of intruders would regularly reject the phone’s owner as well. So we need to find the best compromise for each specific use case. With smartphones, we err on the side of ease of use, meaning that the devices almost always open for their owner. The current error rate – that is, the number of times the system allows an intruder to unlock a phone – is once per 1,000 attempts. On the other hand, for biometrics systems that control access to very secure locations, such as nuclear plants, we err on the side of security, which means that authorised people often need to attempt to gain entry multiple times."

And what happens if the system is hacked? "Biometrics systems are IT systems just like any other, with one additional aspect: they capture biometric data. That means that they can be attacked by hackers, like any other IT system, but can also be subject to ‘presentation’ attacks of varying degrees of sophistication. For facial recognition, hackers could print a photo and hold it in front of the camera or wear a mask."

In fact, that’s exactly the type of attack Idiap works on. In 2020, the Institute created highly realistic silicone masks, costing 4,000 Swiss francs, to test the limits of facial recognition. "We’re creating increasingly complex attacks to expose the vulnerabilities of each system, and then we build our defences," says Marcel. "Faced with the same attack, two different smartphones wouldn’t react in the same way, for example."

With the development of artificial intelligence, the rise of deepfakes – audio or video recordings created by AI – is a concern for the biometrics industry. Several voice recognition systems have been fooled by AI-generated voices. And as for facial recognition, "it’s possible to attack the system between the scanner and the software by injecting an AI deepfake video. This deepfake then replaces the video that should have been provided by the camera. We’re working on improving security for that as well."

Given this context, should the general public be concerned with the security of biometrics? "Many people publish photos, videos and personal data on social networks and at the same time are afraid of biometrics," says Marcel, wryly. "It’s contradictory and illogical, because you no longer control any data you post online, which poses much more of a risk than the use of biometrics."

But what happens if someone’s biometric data is stolen? "For smartphones that’s unlikely. The data is stored locally on the device inside a chip that destroys itself if you try to force it. On the other hand, when biometric data is stored in databases, that can be stolen. If that happens, we need to find ways to limit the breach, in particular in a way that ensures no raw data is preserved."