The ruthless universe of outer space

The global space economy could double its current size to clear the symbolic $1 trillion mark by 2030. But strangely, most space stocks are struggling. Time to invest?

By Bertrand Beauté

A huge convoy heading for Kyiv. Horrors in the streets of Bucha. Destroyed buildings in Soledar. Since February 2022, satellite photos have documented the war in Ukraine in near real time. Images show weapons, buildings and the desolation of the battlefields with minute precision. And they are all stamped with a copyright: Maxar Technologies. This US company created in 2017 is now all over the headlines.

Maxar’s new-found fame is no fluke. It points to an important shift in the use of outer space. "For decades, the space industry developed around government-run space agencies (NASA in the US, ESA in Europe and Roscosmos in Russia), which worked with long-standing defence contractors (Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Airbus, Dassault)," says Maxime Puteaux, a space industry consultant with the firm Euroconsult. "But since the beginning of the 21st century, a private-sector space industry has emerged, with a bevy of startups setting out to explore space."

This US-born industry has been dubbed NewSpace, in contrast to the Old Space economy, which is perceived by the newcomers as an ageing and rigid industry. "The plummeting cost of space access triggered the NewSpace movement," says Emmanuelle David, executive director at EPFL’s Space Center, in the interview she granted us. "It gave small companies and research laboratories, the opportunity to launch their own satellites, something that was previously reserved for governments before that."

In 2021, SpaceTech Analytics counted more than 12,000 space tech companies. This number has exploded up from only a handful of firms two decades ago. The plethora of new players shows through in the figures.

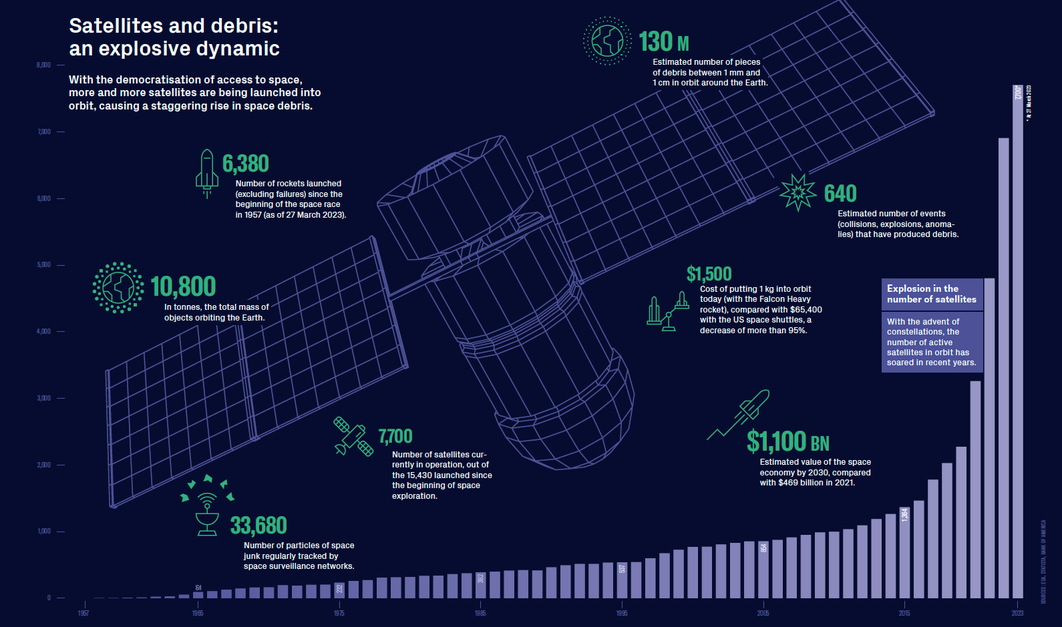

In 2022 alone, 180 rockets were sent into space, 44 more than in 2021 – a record-breaking increase

An article in the journal Nature estimated that in 2022 alone, 180 rockets were sent into space, 44 more than in 2021. A record-breaking increase. For more mind-blowing statistics, 2,469 satellites went into orbit in 2022, a 36% increase from 2021 (1,813) and almost double the number in 2020 (1,272). And that’s not all. A Euroconsult study published in December 2022 predicts that nearly 24,500 satellites will be launched between 2022 and 2031, i.e., an average of 2,500 per year. This would bring the global space market to $1.1 trillion by 2030, up from $469 billion in 2021, according to a Bank of America report in January 2023.

To accelerate their development and capture a share of this market, many NewSpace firms have gone public, especially in 2020 and 2021. But so far, performance has been bleak, and most NewSpace stocks have crashed. The share price of Astra, a US company listed in 2021, has lost 98% of its value. BlackSky and Satellogic have experienced similar fates, with their shares falling 90% and 60% respectively since their IPO. The list of disappointments is long.

Is NewSpace just a financial bubble bursting in mid-air? "NewSpace has sound fundamentals," says Maxime Puteaux. "What is happening is a market correction that is weeding out companies that wanted to rush things by entering the stock market via Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs), whereas they had no mature products to launch to market. They sold unrealistic forecasts, making small-time investors believe that they could get rich with space. When these companies couldn’t deliver on their promises, their shares collapsed." Sometimes spectacularly, like Virgin Orbit. Founded by businessman Richard Branson, the company that designs rockets for launching small satellite payloads went public in 2021 via a SPAC and filed for bankruptcy in April 2023. Just one of many in a string of failures.

Thomas Coudry, head of Tech Equity Research and NewSpace specialist at Bryan, Garnier & Co, believes another reason has caused the stock market debacle: "All tech stocks suffered in 2022 and NewSpace was not spared. The fall was even harder as most of the players in this sector are early-stage companies with huge financing needs to develop. The blow of interest rate hikes has been particularly harsh for these companies."

"Many companies have cropped up in recent years. The competition is fierce. There won’t be room for everyone"

Thomas Coudry, analyst at Bryan, Garnier & Co

However, a few actors have managed to emerge relatively unscathed. Stock of US satellite operator Iridium Communications, listed in New York, has risen by over 80% in a year. "The current period will be tough for the most unstable NewSpace companies," Maxime Puteaux says. "But those that have the capacity to deliver a product quickly with the lowest possible investment have a clear advantage."

Given these circumstances, specialists expect a wave of mergers and acquisitions in the sector. "Many companies have cropped up in recent years. The competition is fierce. There won’t be room for everyone," says analyst Thomas Coudry. He recommends closely tracking companies that receive public funding. "Government orders will remain high in the space industry, especially in defence, which will be a key factor over the next few years. The war in Ukraine has heightened awareness of state sovereignty, and defence budgets have augmented sharply. NewSpace companies with exposure in defence will therefore be thrust upwards." Maxar Technologies’ shareholders would not argue otherwise. In December 2022, they agreed to sell their stake in the world’s leading provider of space solutions, which works with the US military, to private equity firm Advent International for $6.4 billion, a 129% premium per share.